The search for Jewish food in London's medieval Jewry

An analysis of the animal bones from 10th to 13th century pits at Milk Street (MKL76)

John Schofield and Rebecca Gordon

In 1976–7, the Department of Urban Archaeology of the Museum of London carried out excavations at 1–6 Milk Street, EC2 (site MLK76) which revealed several medieval properties and 121 pits and from the late 9th century to the 13th century. The pits contained a wide array of archaeological finds including pottery, leather shoes, wooden bowls, metal and bone objects, textiles (linen, cloth and silk) and animal bones. The details of the excavation were published in Transactions 41 (Schofield et al 1990).

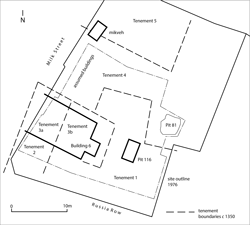

In December 2019, LAMAS granted John Schofield and Rebecca Gordon £3,500 to publish all the medieval faunal collection from the Milk Street excavation to follow and match the original report of 1990. Rebecca has analysed the animal bones from one of the most important pits, Pit 81 (on the plan, Fig 1; what it looked like, Fig 2) on a grant from the City of London Archaeological Trust (CoLAT). It was evident that she should continue with the analysis of all the animal bones from the 121 pits.

There are two objectives: to study the animal bones in the pits, to observe characteristics and changes in human diet; and to see if we can identify Jewish food practices (sometimes called foodways).

Milk Street is within the heart of London's medieval Jewry, north of Cheapside. Jews had taken residence in this area by the 12th century. The boundary of the London Jewry was never fixed and Jews and Christians coexisted within it until the expulsion of the Jews in 1290. Three tenements discovered in the 1976–7 excavation were occupied by Jewish families in the 13th century and possibly before (Schofield et al 1990, 131–44). After the excavation and during the redevelopment of the building constructed on the site in 1978, a mikveh or Jewish ritual bath was discovered which belonged to one of the Jewish families on the street (Blair et al 2001; its position is shown on Fig 1). This had survived, just outside the area excavated in 1976–7.

Milk Street is within the heart of London's medieval Jewry, north of Cheapside. Jews had taken residence in this area by the 12th century. The boundary of the London Jewry was never fixed and Jews and Christians coexisted within it until the expulsion of the Jews in 1290. Three tenements discovered in the 1976–7 excavation were occupied by Jewish families in the 13th century and possibly before (Schofield et al 1990, 131–44). After the excavation and during the redevelopment of the building constructed on the site in 1978, a mikveh or Jewish ritual bath was discovered which belonged to one of the Jewish families on the street (Blair et al 2001; its position is shown on Fig 1). This had survived, just outside the area excavated in 1976–7.

Archaeological evidence for London's Jewish community has been sparse and the recovery of Jewish material culture from the City has been sporadic. Surprisingly, the potential of faunal remains to detect Jewish dietary practices remains to be fully explored using assemblages excavated in London. Analysis of faunal remains from European medieval sites with Jewish populations have shown how animal bones can be a useful indicator for Jewish occupation. This is because the slaughter, preparation and consumption of meat must adhere to the laws of kashrut to be considered as kosher (fit for Jewish consumption) which includes the exclusion of, for example pork, rabbit, horse, eel, shellfish and hindlimbs of the main domesticates (unless the latter have been processed by a kosher butcher).

The LAMAS grant will allow us to determine what Jewish and Christian Londoners ate in the 9th to 13th centuries, and the analysis will note the bones of fish (figure 3), pets, vermin, and exotic species.

The recording of the bones will be undertaken by Dr Rebecca Gordon. She completed her PhD in zooarchaeology at the School of Archaeology and Ancient History, University of Leicester in 2015, and is currently a freelance zooarchaeologist and independent researcher.

John Schofield will provide the wider context for the study; he was the original site supervisor for this part of the sequence (the post-Roman) on the 1976–7 excavation

Further Reading

Blair, I, Hillaby, J, Howell, I, Sermon, R, and Watson, B, 2001 'Two medieval Jewish baths – mikva'ot – found at Gresham Street and Milk Street in London', Trans London Middlesex Archaeol Soc 52, 127–38

Schofield, J, Allen, P, & Taylor, C, 1990 'Medieval buildings and property development in the area of Cheapside', Trans London Middlesex Archaeol Soc 41, 39–238

"Face of a Plantagenet child bride" : LAMAS in the Sunday TimesThe 67th volume of the LAMAS Transactions (2016) features a piece by Bruce Watson and William White on the child princess, Lady Anne Mowbray, married into the House of York at the apex of the Wars of the Roses at just the age of eight, and whose skeleton was found in the '60s beneath the street of Minories in East London. The article examines past and present knowledge on the child's skeletal remains, and its findings were picked up by The Times (published in print on November 25th 2017). Read it on The Times Online, or check it out below! |

The new reconstruction of Lady Anne Mowbray’s face by Amy Thornton for John Ashdown-Hill |

Face of a Plantagenet child bride

Norman Hammond, Archaeology Correspondent. The Times.

The face of a Plantagenet princess has been reconstructed from her skeleton, while her bones and hair have yielded data on her stature and health at the time of her death in 1481. The remains of Lady Anne Mowbray also have the potential to illuminate one of English history’s greatest mysteries: the fate of the Princes in the Tower. Lady Anne was the daughter of the Duke of Norfolk, his only child and, after his death in 1476, the greatest heiress in England. Edward IV got papal leave to have her married to his younger son, Richard, Duke of York, in 1478, although she was related to the Plantagenets and both were legally too young to marry. However, Anne died before her ninth birthday, leaving Richard a widower at the age of eight. Interred in Westminster Abbey, she was later ejected by Henry VII in 1502 when he built his own mortuary chapel at the eastern end. Her coffin was then reburied in St Clare’s Abbey near Aldgate, the home of her mother, the dowager duchess of Norfolk.

In 1964 a digging machine uncovered her vault while clearing wartime bomb damage, as Bruce Watson reports in Transactions of the London and Middlesex Archaeological Society. Dr Francis Celoria of the London Museum (now the Museum of London) realised from the finely engraved plate on the lead coffin who was inside it and set up a multidisciplinary scientific investigation to study her remains. A fuss in parliament and in the press about the failure to obtain a burial licence curtailed the study, and its results have never been fully published. They do, however, show that she was about 4ft 4in tall — small for a modern child of nine, but the norm until the late 19th century due to deficiencies in diet. Her hair had high levels of arsenic and antimony, perhaps from her medicines, and she seems to have suffered from ill-health. When her body was prepared for burial her shroud appears to have been treated with beeswax and decorated with gold leaf or thread, and a separate cloth covered her face.

“Individuals like Anne who are precisely dated are vital, so her remains are of international importance. A recent survey of more than 4,600 juvenile burials from 95 British medieval and early post-medieval sites included no named individuals”, so their precise dates of birth and death could not be ascertained, Mr Watson notes.

Of more general interest was a congenital dental anomaly — missing upper and lower permanent second molars on the left side — that Lady Anne shared with the two juvenile skeletons found in the Tower of London in 1674, assumed to be those of her husband, Richard Duke of York, and his brother, King Edward V (the Princes in the Tower). The bones, which are interred in a splendid marble urn in Westminster Abbey, have not been examined since 1933, but reanalysis of photographs has suggested that the two juveniles were 13½-14½ and 11½-12½ years old when they died. If they were indeed the bones of Edward V and his brother, then the overlapping spans show that they could have died in 1484, pinning the blame on their uncle, King Richard III (The Times, May 21, 1987). A slightly later date in the reign of Henry VII is also possible, Mr Watson says, but “the debate over the identity of these undated juveniles will continue until their remains are re-examined. They could be radiocarbon dated and DNA extracted to confirm if they are related to each other and to Richard III.”

Since Richard’s skeleton was discovered five years ago and intensively studied before his reburial in 2015, his DNA is available and a link through the male Plantagenet line could be established, Mr Watson notes. Despite many suggestions in recent decades that the putative remains of the Princes in the Tower should be subjected to the minimal sampling needed using modern technology, the authorities at Westminster Abbey (a “Royal Peculiar” outside the Church of England’s control) have resisted.

“It is extremely rare for the remains of named pre-Reformation individuals to be studied in England,” Mr Watson says. Richard III’s rapid interment without perhaps even a shroud was “completely untypical and can be attributed to the unexpected manner of his death”. Anne Mowbray’s burial was that of an aristocrat with royal links and “undoubtedly of value to our understanding of death and burial during the late 15th century”. The new reconstruction shows us how her princely bridegroom may have seen her.